A memory-efficient data structure for geolocation history (rev2)

In this blog post I'll cover how I built a memory-efficient data structure for storing location history data.

Some Rust details will also be explained.

This article is a rewrite of my previous one, after taking into account feedback from Reddit and further researching the topic.

Motivation

My DSLR camera has no GPS built-in. Evidently, photos from it don't include geolocation-based EXIF tags.

If only my location history were stored somewhere, so that I could update photos with the correct data...

Unsurprisingly, Google knows where I am, where I've been and where I'm going to be. They even allow me to export this data.

The problem is that the exported JSON weighs ~1GB. My computer has 16GB of RAM so it can all fit in memory, but we certainly can store it more efficiently.

JSON parsing

For reference, here's what the JSON looks like:

{

"locations": [{

"latitudeE7": 435631892,

"longitudeE7": 26848689,

"accuracy": 56,

"activity": [{

"activity": [{

"type": "STILL",

"confidence": 100

}],

"timestamp": "2014-01-09T00:48:24.424Z"

}],

"source": "WIFI",

"deviceTag": 1348159918,

"timestamp": "2014-01-09T00:48:24.751Z"

}, {

"latitudeE7": 435631881,

// ...

Deserializing a JSON file into a struct results in something that is certainly lighter than the JSON string.

The reason for this is that a string with the value "2022-10-22" needs more bytes than, say, its equivalent Date object.

The latter can simply throw away the hyphens, for example. Additionally, the number 10 can be represented with 4 bits instead of using two chars, which occupy at least 8 bits each.

So moving away from a textual representation is the first step in our journey.

The simplest way to deserialize this data is to put its contents into a String and then pass it to your Json deserializer or choice.

The problem of this approach is that the String will occupy ~1GB of RAM, even if for just a couple of seconds.

Ideally, we should have a stream of data and keep deserializing small chunks at a time.

I'm pretty sure there are some libraries out there capable of that but I decided to simply iterate over each line of the file, extract relevant data and ignore the lines I wasn't interested in.

Do we really need to store everything?

The most straightforward structure for our purposes is a sequence of DataPoints, where DataPoint has datetime, latitude and longitude:

[

(DateTime(2022,10,22,10,45,32), 27.5226335, 43.552225),

(DateTime(2022,10,22,10,46,21), 27.5226382, 43.552237),

// ...

]

But isn't there some redundancy? The data is clearly not random.

There are some assumptions we can make to help us design a better data structure:

- Data points are sorted by time

- Neighbor data points are very similar

- unless I'm on a plane, my speed is at most 100 km/h, so in a minute I'll travel less 2 km

- on foot I'll travel just a few meters

- Most of the days I stay inside a circle of 3km of radius

- One data point per minute is more than enough

- Errors in position up to 15m is something I'm OK with

Estimating size of straightforward solution

Throughout this post, let's consider 2.5 years worth of data, including 345k data points.

Each data point consumes 64 bits for the timestamp and we can store each coordinate with a f64.

In total we need ~11.8 MB (if you did the math and think this off by ~50% please see this section).

How many decimal places do we need to represent a coordinate?

First let's try to understand how much each decimal place contributes to precision.

A quick search on Google gives us the following:

- The first decimal place is worth up to 11.1 km

- it can distinguish the position of one large city from a neighboring large city

- The second decimal place is worth up to 1.1 km

- it can separate one village from the next

- The third decimal place is worth up to 110 m

- it can identify a large agricultural field or institutional campus

- The fourth decimal place is worth up to 11 m

- it can identify a parcel of land

If we want to have errors less than 15 m, we need to be able to correctly represent the latitude and longitude up to the 4th decimal place.

If both coordinates are off by 0.0001° then the error will be close to sqrt(11^2+11^2) ~ 15 m.

How many bits do we need to represent time?

For our purposes, 24 bits would be enough.

However, we don't need to store timestamps.

Instead of having at most one data point per minute, we can have exactly one data point per minute.

It's cheaper to just duplicate data for missing timestamps. The duplication of data is surely unfortunate, but having to spend 24 bits for every minute of data is worse.

The plan

Suppose our data looks like this:

| Timestamp | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|

| 2022-10-15 16h13 | 26.1234 | 43.5678 |

| 2022-10-15 16h14 | 26.1235 | 43.5677 |

| 2022-10-15 16h15 | 26.1236 | 43.5678 |

We could delta-encode it so that all points (except the first one) are just the difference from the previous value:

| Timestamp | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|

| +1 min | +0.0001 | -0.0001 |

| +1 min | +0.0001 | +0.0001 |

The data clearly becomes easier to reason about and is arguably "smaller".

But when using an f32 to represent a number, it doesn't matter if it's 26.1234 or 0.0001: they will both occupy 32 bits. So we need a way to make small numbers occupy less memory.

Finally it would be nice to somehow merge the latitude and longitude columns, so that we can keep track of a single value instead of having to store 2 deltas for each minute.

To recap, the plan is to:

- merge latitude and longitude into a single value

- delta-encode the data

- store small numbers efficiently

Representing 2D data with a single number

The objective here is to come up with a function f(pos: (f32, f32)) -> u32 and an "inverse" function g(n: u32) -> (f32, f32) such that error(pos, g(f(pos))) < ε, for any valid pos.

In our case, ε = 15 m.

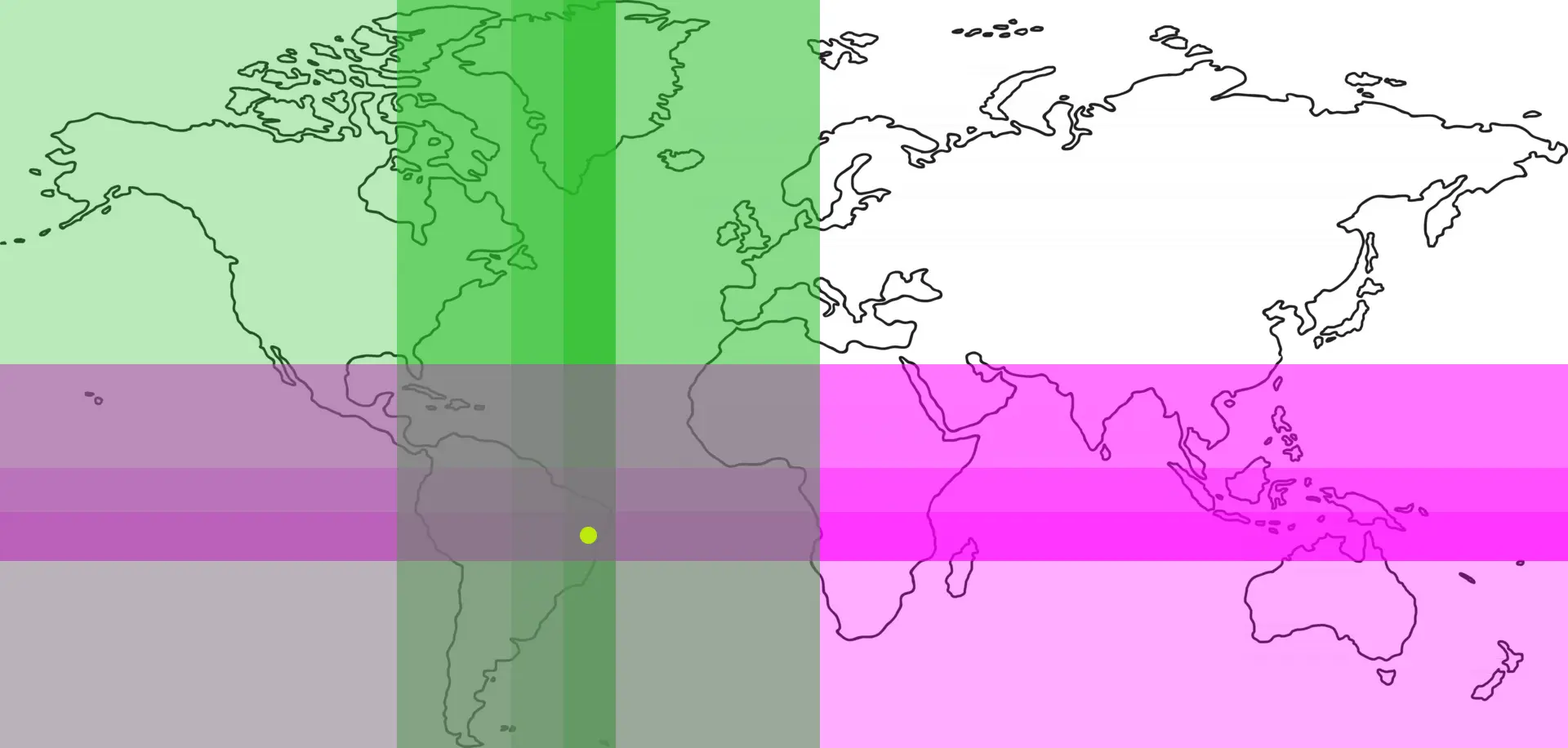

The most straightforward way to do it is like so:

The problem with this algorithm is that the distance between neighbour points isn't necessarily small.

Suppose we move one step to the right. The distance traveled will be one unit. Great!

Now suppose we move one step up. The distance traveled will be grid.cols, which is certainly more than we'd like. This means that moving +0.0001 in latitude could result in a distance of thousands of units, yet we want deltas to be as small as possible.

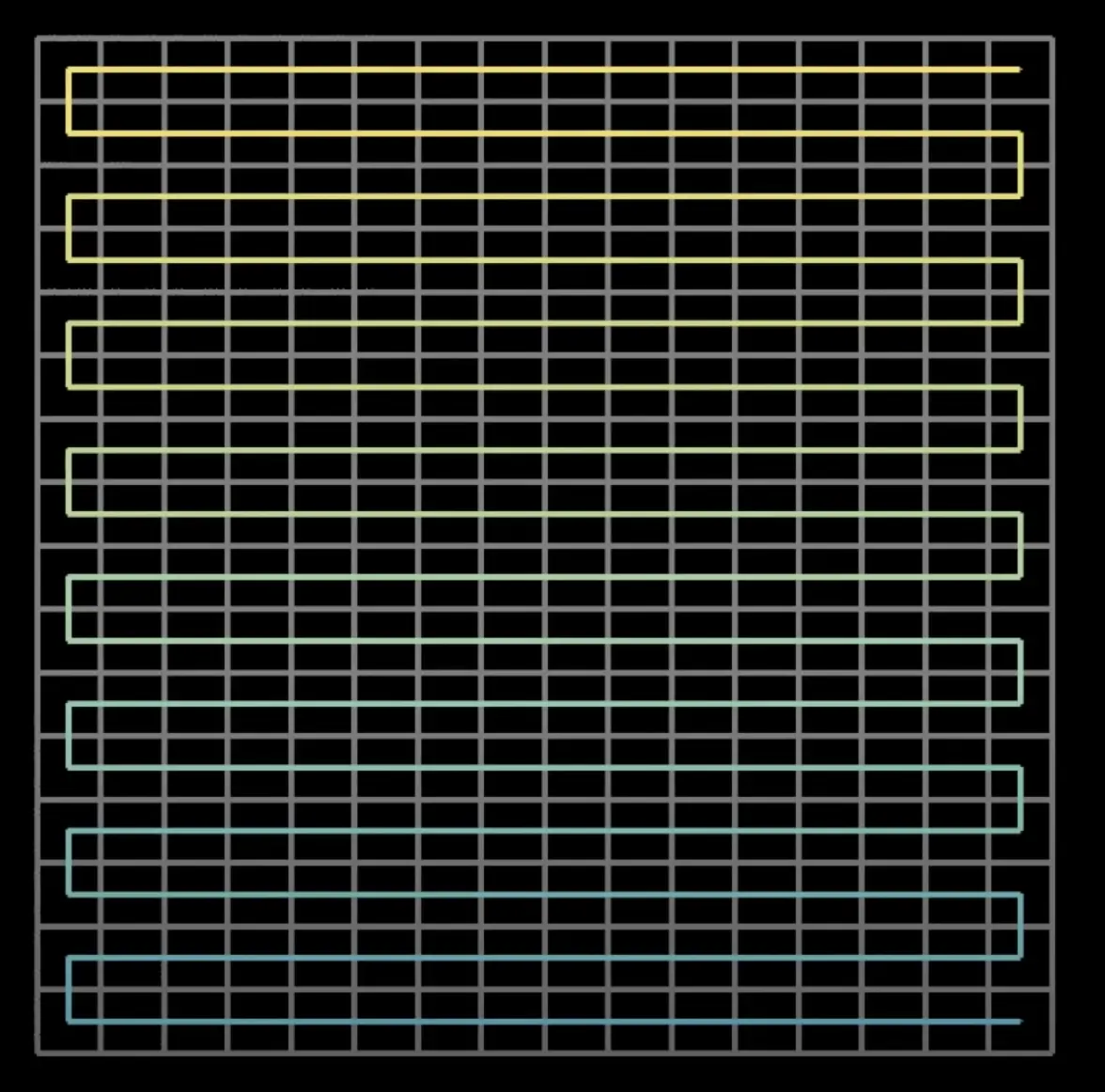

A more elegant solution would be to use Hilbert curves:

Now, if we move one unit, the traveled distance will generally be small, regardless of the movement being horizontal or vertical.

For resolutions big enough, this will remain true for most points, except the ones at "boundaries" (e.g. going from a red cell to a green one).

This video from 3b1b explains the concept of space-filling in detail. It's worth checking it out!

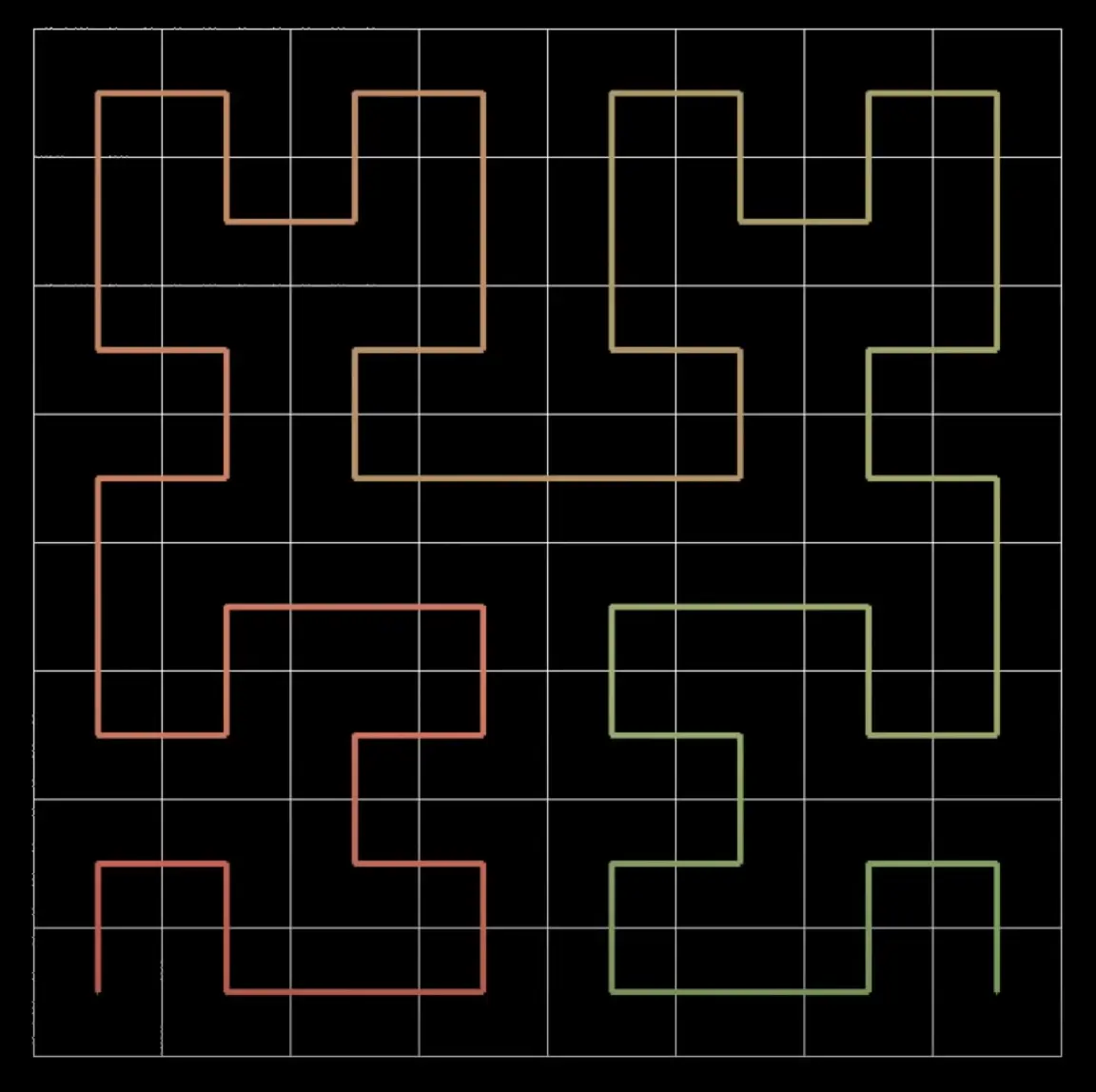

That said, I decided to go with a simpler strategy, which is close to the concept of binary space partitioning.

Here's the idea:

- is our point in the left hemisphere or right?

- if left, set first bit to 0; otherwise, 1

- is our point in the south hemisphere or north?

- if south, set second bit to 0; otherwise, 1

- is our point in the left half of the region in

1or right?- if left, set third bit to 0; otherwise, 1

- is our point in the south half of the region in

2or north?- if south, set fourth bit to 0; otherwise, 1

- ...

Here's an image depicting the process of representing the yellow circle:

One nice property of this algorithm is that, as we take more decisions (i.e. as resolution gets more fine-grained), we're simply adding more bits.

This means we can throw away less significant bits as we see fit.

Storing small numbers efficiently

This paper describes a lot of different methods.

I decided to use a modified version of the Simple8b algorithm because of, as you've probably guessed, its simplicity.

The idea is to divide a u64 into 2 parts: a selector of 4 bits, and a data region of 60 bits.

The selector determines how many bits each number inside data will take.

For example, for selector=15, we store 60 numbers of 1 bit each; for selector=14 (= 1110 in binary), we store 30 numbers of 2 bits each:

4 bits 60 bits

=== selector === | ====================== data ========================

1110 01 10 00 10 11 ... 01

(= 14 in dec) | | └ third number |

| └ second number |

first number 30th number

I made 2 modifications to this algorithm that allowed me to compress data even further.

Modification 1: representing (a lot of) zeros

As mentioned above, we're adding one data point to our data structure for every minute. But what if there's simply no data for an entire month?

The good news is that the deltas will be a lot of zeros, if we decide to simply copy the latest data point over and over.

The bad news is that we'll have a lot of unnecessary zeros.

So I changed the algorithm so that when selector=1, data is the count of zeros we're trying to represent. So let's say that we have 1 billion consecutive zeros. Instead of needing 1 billion numbers to represent this data, we can simply create a Simple8b-compressed u64 with selector=1 and data=1 billion.

Modification 2: not tracking the count of elements

Unfortunately, the Simple8b-compressed u64 doesn't contain the number of elements compressed.

For example, this test fails:

let input0 = [2, 76, 3, 5, 7, 2, 0, 0];

let input1 = [2, 76, 3, 5, 7, 2];

let inverse0 = simple8b::decompress(simple8b::compress(input0));

let inverse1 = simple8b::decompress(simple8b::compress(input1));

// passes

assert_eq!(input0, inverse0);

// fails: inverse1 = input0, with the extra zeros

assert_eq!(input1, inverse1);

This is also unfortunate because keeping track of this count (which requires at least 8 bits), defeats the purpose of compressing: we may save a few bits here and there but, with this cost of 8 bits per u64, perhaps the final size will be bigger than the original.

In Simple8b, a zero means a lack of data, so there's no way to distinguish between trailing zeros or absence of data.

My change was really simple: whenever we try to store a number n, we actually store n+1. Conversely, when retrieving a number m, we actually return m-1 = n.

This way any zeros we find during decompression indicate that the actual data has already ended.

The downside of this approach is that selector=15 (60 numbers of 1 bit each) becomes useless: normally this could only happen if we had a bunch of 0s and 1s. But now a 1 becomes a 2, so this can only be possible if we have a lot of 0s only. In this case selector=1 will be used.

But we would probably not have this scenario of multiple 0s and 1s to begin with: unless I kept moving ~1 cm per minute for a long period of time. 😅

Representing deltas

Alright, so we can now represent both coordinates with a single number and store a bunch of these numbers efficiently.

A position at time i can then be represented as position_i = position_0 + sum(delta_i, i = 0 to i).

But delta_i is a u64, which is an unsigned integer. How can we represent negative numbers?

This is easy. We can simply bit shift to the left and use the least-significant bit to represent the sign:

fn to_unsigned_delta(signed_delta: i128) -> u64 {

if signed_delta >= 0 {

(signed_delta << 1) as u64

} else {

((signed_delta << 1) + 1) as u64

}

}

fn delta(unsigned_delta: u64) -> (u64, bool) {

let is_positive = unsigned_delta % 2 == 0;

let signed_delta = unsigned_delta >> 1;

(signed_delta, is_positive)

}

Getting our hands dirty

Finally, at its core, our data structure will do the following:

fn add(&mut self, time: DateTime, pos: (f32, f32)) -> Result<()> {

self.add_missing_data(time, pos);

let delta = calculate_delta(self.last_pos, pos);

self.fail_if_error_is_too_big(delta, pos)?; // optional

self.push_point(delta);

self.last_pos = pos;

Ok(())

}

Just to be safe, before pushing the latest delta, I'm calculating if the haversine distance is below ε = 15 meters. This is more precise because the the error varies with the distance to the Equator.

Benchmarking

After finishing everything, we can measure how many megabytes our data structure needs.

Let's insert data for the last couple of years into it and measure memory consumption:

input points: 345 k

packed u64s: 56 k

total size: 512 KB

Oversized Vecs

There's something odd with the numbers above: the Vec should be smaller.

If we have 56k elements of 64 bits, the total sequence should have ~440KB, not 512KB.

After some experiments, I realized that the Vecs were bigger than expected by 5% to 100%. In average, they were ~55% bigger.

I then remembered that such data structures usually double their inner buffers when there's no room for a new element.

Fortunately, Rust offers a Vec::shrink_to_fit() operation, which we can call after finishing mutating our database.

After applying this change, the Vec occupies the expected size.

Final results

After fiddling with some thresholds I noticed that, to achieve a 5m precision instead of 15m, the memory overhead is negligible:

input points: 345 k

packed u64s: 62 k

total size: 485 KB

So I decided to set the max error to 5m instead.

Overall we reduced memory footprint by 24x, compared to the most straightforward solution (using a stream for JSON deserialization).

Had we used a String for storing the whole JSON first, the maximum RAM used would be 1900x bigger!

The final code can be found here.

Conclusion

I didn't need to invest so much bandwidth in this optimization: my PC could use 1GB of RAM for this data anyway.

But I learned a lot as part of the process and I ended up with results very efficient memory-wise.

That said, as mentioned on Reddit, general-purpose compression algorithms achieve similar results and simplify our code a lot. Querying is relatively more expensive, though.

But, depending on your needs, perhaps you can just gzip everything and you're good to go!